Before moving to Spain, I didn’t know that churros were considered to be breakfast food. It was a snack often bought at malls in the Philippines with different flavors of dip. My earliest memory of the deep fried savory and sweet treat, paired with a thick chocolate dip, was from Dulcinea in SM North Edsa. The distinct piped and twisted pieces were in a specifically-made carton for takeout, so you can enjoy them without fuss. My eldest brother, Kuya Pom and my now sister-in-law Ate Paula, often got these for me as a child. If we weren’t eating by the food court, I had the pleasure of taking them with me in the taxi on the way home, careful not to spill any chocolate. My last churros back home was also at that Dulcinea after a bowl of ramen with Dani. Seeing the churros from Dulcinea at their tiny kiosk in front of the restaurant often excited me as years went by, even when I passed by less—or when La Lola Churrería became a thing, and then eventually disappeared, too. Ready-to-fry versions became available in groceries, but it’s never quite the same as freshly fried ones. Churros back then were a special, once-in-a-while treat that took a little bit of exploring to find.

Chocolatería San Gines in Madrid is the oldest establishment for churros in Spain, operating since 1894. I’ve often daydreamed about what it would be like when I finally came to Madrid, sitting outside in the sun with a plate of churros and chocolate from San Gines, reading a book. In reality, the place was so packed and the queue was neverending that I just went back later in the afternoon with my friend Cliff after exploring Museo Nacional del Prado. We were hungry and tired from all the walking, they sat us at a small table inside their extension cafe. The line went on. We ordered two cafes con leche, and for my first churros in Spain, it wasn’t bad. Pricey, but of course, when in Madrid. It’s really never as it seems, but reality didn’t disappoint me, either. It was just different. My first few days in Madrid were a mixture of awe and panic, I took everything in like an excited tourist but also grew anxious of how I’m going to get by the next few years. Of course, a big city like Madrid is always so intoxicating at first, so learning how their Metro system worked was so useful. There would be more churros to try the next time around.

When I made it to Sevilla, I discovered that the town I live in has two churrerías, but they were somehow always closed whenever I passed by. I studied Spanish for two years, both formally and by myself (with some help from the green owl), but it took a few days before I was confident in my skills to talk to the locals freely. Upon asking the owner of the Papeleria, I found out that these churrerías only open during weekend mornings. I got to know the difference between los churros and las porras, and I was pleasantly surprised at how cheap they actually were in local shops that aren’t usually crowded by tourists. I made it a little tradition for myself to get churros at least once every weekend; to try them whenever I encounter a bar with a sign that says, “tenemos churros con chocolate” or a churrería (sometimes called calentería here in Andalucia) I haven’t tried yet. Of course there were a few hits (shops that made their own churros fresh) and misses (those that served ready-made ones from the grocery or overcooked their portions) but there’s nothing like seeing it all in action: the smell of fried food in the air, big vat of hot oil, churro-churning apparatuses, and how they cut through a big wheel of porras. Contrary to what we know of churros back home, the chocolate for churros here is a usually served by the cup. It’s for dipping and also drinking afterwards, but you can also choose to go without.

The prices for churros in these churrerías vary, and while the ingredients are practically the same for every recipe, the nuance lies in their cooking technique, portion sizes, and customer service. Aside from all the possible adventures you can take while getting to know Spanish food, like sampling tapas, trying out different breads, or dethroning the stereotypical sangria for a tinto de verano (I take mine con limon)—comparing churrerías helps you get familiar with the local food scene and gives you insight on how the community keeps establishments going for decades.

Buenas! Una ración de churros con chocolate, porfa. Gracias.

Eat a bag of churros plain or sprinkled with sugar, with chocolate or coffee, and you’re all set. The Spanish hot chocolate is so distinct that they even sell them in groceries so you can recreate them at home, my personal favorite being the chocolate brand Paladin (specifically for churros), not to be confused with Colacao, a popular chocolate drink in my pantry and the cafeterías. Ask for chocolate and they’ll give you the thick version made for churros; the one most akin to Swiss Miss, they call Colacao.

Of course, while it sounds amazing to have churros every day for breakfast, they’re not exactly the healthiest choice. For that reason, it’s always good to have variety. Take bagels, for example. Madrid’s bustling with bars and restaurants of different cultures, so this New York gem has its place in Chamberi. When done right, bagels are a filling and delicious, no matter what you put in between the slices. It’s a little tough on the outside but chewy on the inside, and there’s other flavors to be had, depending on the toppings. Fresh from the oven, they’re golden even on their own. It’s crucial to have them fresh so it doesn’t get stale. It’s a thrill to choose with which schmear or meat to pair if I’m eating it as a sandwich. In Madrid, I tried their typical mixto: turkey with cream cheese on their sesame bun. Wida got hers with bacon, cheese, and egg. I also tried out their ‘American’ hot chocolate. It’s so fun to not be afraid of carbs!

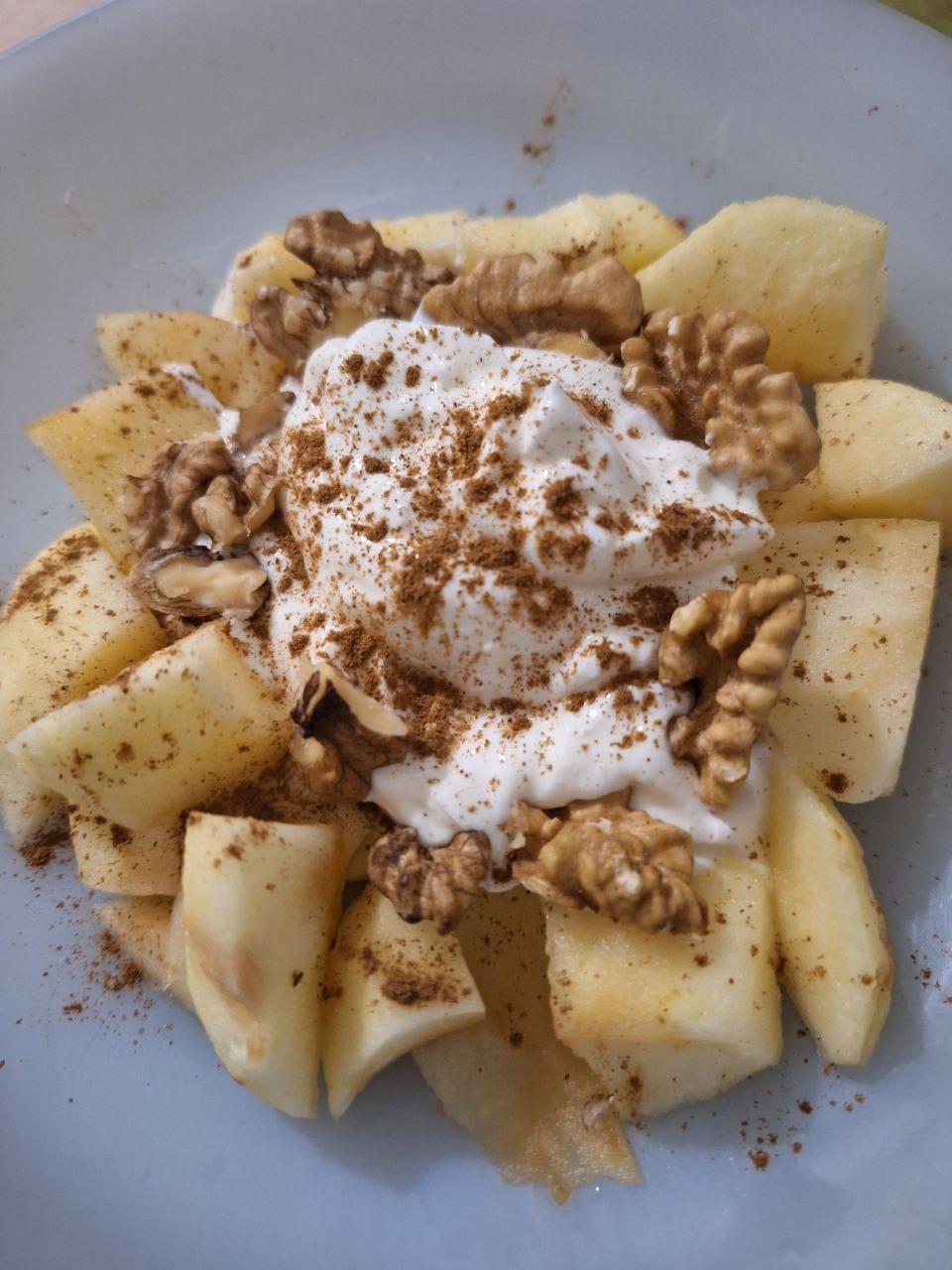

When I’m preparing quickly in the morning, I usually go for a cereal and soy milk bowl or greek yogurt with apples, cinnamon, and nuts. These days, I add a little strawberry jam. The recreo in school is at 11 in the morning, and sometimes they refer to this period as “second breakfast” or just breakfast, if they haven’t had any to eat. It’s true that the meal times in Spain start a little bit later than other cultures, and I do find myself unintentionally also having lunch around 3pm or dinner at around 9 or 10pm. The food culture here is interesting, and in my first few months, I’ve only just begun exploring their gastronomy. It’s been nice having traditional homemade Spanish meals, or becoming a part of faculty parties where they cook arroz con carne o setas, as well as interesting salads and a good selection of vinos y cervezas paired with potato chips, crackers, olives, meats, or cheeses. The need for dessert or a piece of fruit afterwards is more opportunity to bond. I’ve eaten more oranges here than my last few months in Quezon City. It’s always fascinating to discover new flavor combinations I would have never tried out on my own before coming here.

I’ve made friends with the staff of the school and they only speak Spanish, so it’s a chance to practice my conversational skills. I’ve also been sampling the cafetería menu when I find myself with free time after a class and hungry. Sometimes, I opt for a tostada, but if I’m hungry, a bocadillo is much preferred. One thing I haven’t quite gotten used to is the simplicity of what they put in their sandwiches or toasts. While I’m used to various flavors a la Subway, club sandwiches, or pandesals loaded with palaman back home, there’s less to be had on a Spanish tostada or bocadillo—ketchup or mayo are not used as often, and cold or dry cuts like york or jamon are frequent. Pavo or pollo, also ideal. Once, at a bar in town called Casa Pedro, I asked what the “manteca colora” is from their menu, the one they boast of as their best product. I expected an explanation in rapid fire Spanish, but the guy went out back and returned with small pieces of bread smeared with an orange greasy blob for us to try. Manteca colora is apparently lard with spices, paprika, and meat. It’s typical in Andalucian tostadas, and maybe another time, I’ll come back for a fuller experience.

Aside from churros—there’s a special place in my heart for a good tostada. Olive oil on a crunchy toasted bread is delicious on its own (my stomach thanks me for laying off the butter), but once you find your perfect combination, I find it to be a hearty breakfast. I’ve since been appreciating the variety of bread, meat, and cheese that Spain has to offer. When I taste a particularly amazing blend of flavors from just these ingredients together without condiments, save for a splash of olive oil, I begin to understand the way the Spanish highlight the quality of their products: no frills, just fresh ingredients. I found it all a little dry, until I discovered how much of a game changer olive oil can be outside of pastas and salads. I don’t usually like vinegar, but trying a mixture of olive oil and balsamic vinegar with a crunchy bread works as appetizers. The best way to try tostadas for breakfast is at local cafeterias or bars, and it takes a bit more effort to know which one is the best as opposed to Google-searching and ending up in tourist traps. They’re reasonably priced, and each place has their own versions—buen aprovecho!

Breakfast is my favorite meal of the day. Even as I immerse myself in eating breakfast like the Spanish, I still feel that I bring a little bit of Filipino in me to the table. I still have rice in my patry and sometimes buy easy-to-cook ulam to pair with an egg. I fry my rice with garlic. I took with me a tocino mix from Madrid the first time I went to a Filipino market there. I echo Doreen Fernandez when she wrote about the versatility of a Filipino breakfast— from making use of leftovers or preservation techniques for meals, and filling up workers with the needed strength, “It brings the family together at the start of another communal day; it opens the morning in grace and togetherness.”

I will forever be a silog enthusiast, and a believer that your choice of ulam for silog says a lot (I love longganisa simply because it’s always different in every restaurant either garlicky or sweet, but a crispy and a little salty corned beef with potatoes and onions is top-tier). I reminisce strongly about my mother making breakfast every day before leaving for work. It would offend and worry her to go out of the house without eating anything first. It’s a reminder, also, that she cares for us so much that she’d wake up at an hour earlier than she has to just to get us food. When we woke up a little later when she’s already at work, the food would be a bit cold, but I was always grateful to know there’s usually food waiting for me. On the weekends, we ate breakfast together as a family, where we mixed and matched ulam with our sinangag and egg. My mother knows that I adore a good scrambled with tomatoes or a crispy over-easy, but she also boils an egg for me every day for breakfast without even asking. Mcdonald’s breakfast meals in the Philippines also have a special place in my heart, and I can never go without a hashbrown.

Overpriced brunch places are out, local silog restaurants are in—my top favorites in Quezon City being Lola Idang’s and Kanto Freestyle Breakfast. There’s something so magical about a 20-peso bag of hot pandesal or hearing the familiar call of “Taho!” from our suki so we could have piping hot and sweet taho in our own mugs. It’s a breakfast culture I am immensely proud of and continue to honor.

Most of the time, really, I miss the food back home. It’s what keeps me so strongly-tied to our culture. It’s never the same anywhere else. However, there’s a little more to love about the life I live now when I get myself a good Spanish breakfast. It’s more than just satiating hunger from a full night’s rest—getting to expand my palate, interacting with locals, being closer to the cultural experience so that I may feel a sense of belongingness…really, what better way is there to start the day?

NAKAKATAKAAAAAM (imy all the time!)